Read in

Like a scene from Dune, the French–Moroccan startup Sand to Green aims to turn the desert from threat to food producer. It’s a lesson Australia also needs to learn. “If we were to try to produce all the food we will need in 2050 using current production systems, the world would have to convert most of its remaining forests,” Tim Searchinger of the World Resources Institute says.

Over 90% of Morocco is located in an arid to semi-arid climate, and two thirds of the country is in desert. The country is “highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Water scarcity, food insecurity, desertification, and shoreline erosion are all already growing problems. The country loses about 31,000 hectares of forest each year … due to fires, deforestation for firewood and/or construction wood, and the extension of crops, cereals, and pastures.” Desertification through rising temperatures and more frequent and severe droughts result in the loss of topsoil, which has taken hundreds of years to build up.

“Sand to Green aims to create new arable land in Morocco, while continuing to fund research and development (R&D) of desalination and measuring soil re-fertilisation. For the first quarter of 2023, the start-up is announcing the creation of 20 hectares of arable land for agriculture in the south of the Cherifian kingdom,” Afrik 21 writes.

Several investors, including Katapult and Catalyst Fund, have contributed one million dollars to advance the project to “green deserts through agroforestry and water desalination.”

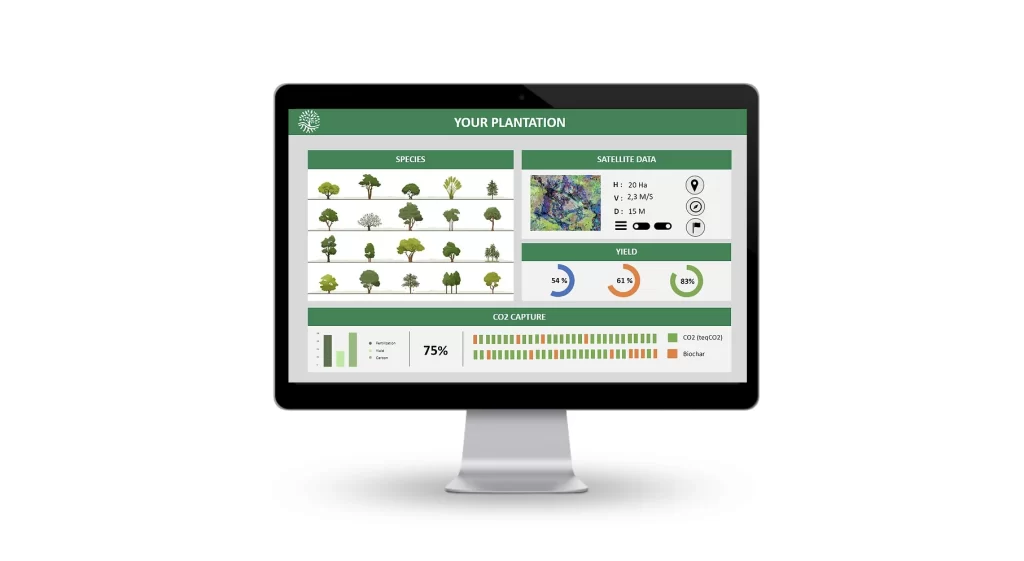

“We will offer these plantations as green investment products to investors, while taking care of their development and associated services such as agronomic expertise, operations and commodity production,” explains Benjamin Rombaut, managing director and co-founder of Sand to Green. “This will allow them to finance soil regenerating and ecological agriculture or agroforestry that does not create deforestation, but ensures similar or even higher yields than conventional agriculture.”

The startup is using drip irrigation with desalinated sea or brackish water. Satellite data will enable daily monitoring and management. Sand to Green has been field testing its techniques for the past three years in the Guelmin-Oued Noun region of Morocco. The farming systems have proven themselves resilient.

The Catalyst Fund states: “The Sand to Green model is founded on three interconnected pillars:

- Large tracts are farmed with adapted food-producing trees that are maintained with Sand to Green’s agroforestry approach, which maximizes production and yield through a combined strategy of different cropping patterns. Their model combines three layers of trees with different intercropping. All varieties chosen require small amounts of water, are salt-tolerant, have high value for local communities, strong carbon absorption, and soil regeneration capacities.

- Climate-smart irrigation systems powered by solar energy. The farms are irrigated through three connected systems: Sand to Green’s reverse osmosis technique and solar-powered desalination units produce fresh water from seawater and brackish water with minimal environmental impact and optimized costs. That water is delivered via drip irrigation techniques that bring the water necessary for plant growth directly to the root system, minimizing evaporation and water loss, and reducing overall water consumption by 30 to 50%. Finally, a hydro-shrinker solution maximizes the use of water thanks to a natural hydro-retainer, biochar, capable of increasing the quality of soils, storing carbon, and also retaining water to avoid its runoff and increase water retention.

“The third and final pillar is customized agroforestry software for farmers to create and manage farms in arid environments. This enables day-to-day management facilitated by field and satellite data.”

Reversing the desertification process will benefit populations under threat of displacement due to drought, soil erosion, floods and other conditions exacerbated by climate change. Sand to Green’s model fights food insecurity and regenerates land. This could reduce the emigration of large populations from Africa which we see nightly on the news.

Sand to Green uses nature-based solutions to restore the land. The cultivated plants remove carbon from the atmosphere and produce oxygen. The carbon is stored in the plant mass and also the soil, improving the soil quality. Local inhabitants gain time to adapt and become more resilient.

Sand to Green’s first farm has attracted diverse forms of life — bees and other insects, as well as birds and rabbits coming back to the land that was once desert. Sand to Green can restore natural biodiversity.

“Overall, the Sand to Green approach meets the challenge of climate change adaptation by offering better yields, enabling greater resilience to extreme events (better soil water retention capacity, increased resistance to diseases, etc.), strengthening food security (healthier and varied diets, increasing producers’ incomes, etc.), and by promoting the biodiversity of crops, animals, and landscapes.”

In contrast, the Great Green Wall project is failing to meet its objectives in the Sahel countries due to insecurity in the regions proposed. “Launched in 2007 by the AU, the initiative initially envisaged the continuous planting of millions of trees over a 15 km wide strip from Senegal to Djibouti. In 2013, the vision was reoriented towards a broad programme of sustainable ecosystem management and improving the living conditions of rural populations affected by land degradation. The project’s goals include restoring 100 million hectares of land, capturing and storing 250 million tons of CO2 through vegetation by 2030, and creating 10 million jobs in rural areas while contributing to food security in one of the world’s most malnourished regions.”

After 15 years of work (from 2007), the project is only 20% complete, mainly in Senegal and Ethiopia. The African Union has decided that the project will now extend to southern Africa.

“According to Elvis Paul Tangem, the GGW project coordinator for the AU, it is almost impossible to continue planting trees and restoring degraded land in Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, Nigeria, Eritrea and northern Cameroon because of insecurity and the reallocation of funds to humanitarian aid,” Afrik 21 adds. “We are now moving to areas that are less of a security threat and less prone to conflict,” Elvis Paul Tangem said. “We are aware that Madagascar, Angola, Namibia and South Africa have suffered severe drought and desertification in recent years. The Great Green Wall now extends to these countries,” he added.

In the Sahel regions, desertification increases insecurity and then insecurity increases desertification and stops those trying to halt the trend. It is a vicious cycle — the opposite of the virtuous cycle proposed by Sands to Green. Several African leaders have identified climate change as one of the main drivers of insecurity in Africa. “In my country, we live in constant insecurity, due to many factors that put Sudan at the top of the list for climate vulnerability,” says Nisreen Elsaim, chair of the United Nations Youth Advisory Group.

These two stories emphasize that climate change is not just a problem for one region. We must all work together to resolve desertification and conflict issues for the sake of the individual, the countries, the region, and the entire world.