Read in

Demographic projections have forecast that in the coming decades, Africa’s rate of urbanisation will be the highest in the world. According to some models, the majority of the continent’s population will be urbanised by the mid-2030s at the latest.

As a result, Africa’s cities and food markets offer the largest and fastest-growing market opportunity available to the continent’s 60 million farms.

Parallel increases in per capita income, fuelled by an emerging middle class, are triggering dietary changes. By 2010, the African Development Bank (AfDB) estimated that the continent’s middle class accounted for over one-third of its total population.

Growing per capita income leads to pronounced dietary changes, including diversification from starchy staples to higher-value perishable products such as dairy, meat and horticulture, as well as growing demand for prepared and processed foods.

In their efforts to supply growing urban food markets, Africa’s farmers, agro-industries and policymakers face many challenges. Farmers must find ways to intensify food production amidst increasing land pressure and rising wage rates.

They must simultaneously diversify production to accommodate a growing demand for high-value perishables such as poultry, dairy, livestock and horticultural products.

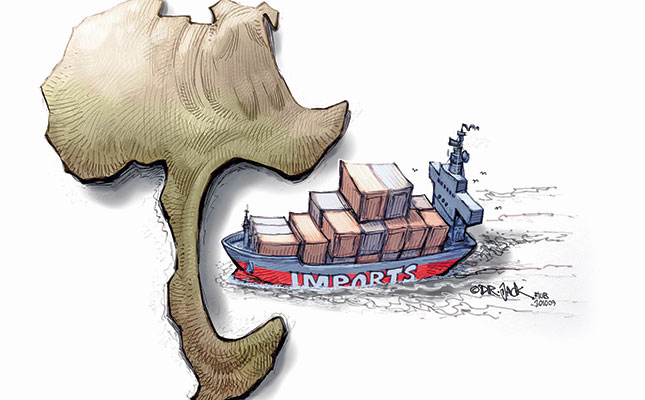

In addition, in the face of mounting food imports from overseas, African farmers, traders and wholesalers have to find ways to drive down the domestic costs of production, storage and distribution in order to remain competitive with external suppliers in Brazil, North America, Europe and Asia.

Africa’s productivity gap

Over the past five years, Africa has imported food worth an average of US$72 billion (R1,18 trillion) annually, down about US$10 billion (R163 billion) per year from the years immediately following the 2011 world food crisis.

While some countries can afford to substitute domestic production with imports, thanks to higher incomes from exports of natural resources (including oil, gold and diamonds) and cash crops (including cocoa and coffee), the same does not apply to the continent at large, as more than 40% of its population is still living below the international poverty line.

Slow progress towards food security has been attributed to low productivity of agricultural resources, high population growth, political instability and civil strife, as well as low yield levels.

Production of the main cereals, which represent 50% of the average caloric intake in Africa, increased 30% overall in volume terms from 2009 to 2018. Wheat production experienced an average annual growth of 2,4% over that period with a 13% increase in yield.

The volume of rice produced also increased, from 23,3 million tons to 33,2 million tons, although average yield declined 11%. Maize production reached 79 million tons in 2017, compared with 60 million tons in 2009.

There are still significant gaps between Africa’s yield levels of maize and rice and the world average. Overall, Asian and South American countries achieved yields 2,6 times greater, and North America six times greater, than the average in Africa.

Average rice yield per hectare in Asia is double, and in North America 3,7 times more, than that of Africa. Improvements in yield levels for maize and rice in Africa have been relatively stagnant over the past 10 years. Wheat yield increased to world levels in 2011 but has remained slightly below average world levels during the past few years.

According to the AfDB, one-third of all calories consumed in Africa are imported, resulting in a negative net agricultural trade balance of US$18,37 billion (R302 billion) in 2019. Overall, the growth of food imports over the past 10 years has averaged 3%.

The volume of intra-regional trade for food items within Africa also remains low; the share of food imports from Africa compared with that of the total imports from the rest of the world decreased from 17,4% in 2001 to 12,6% in 2008, and increased to 15% by 2019, implying a growing dependence on international imported food products as a proportion of the continent’s import basket.

While numerous differences exist in the conditions of production across Africa, some key salient features cutting across most regions and sectors explain Africa’s aggregate performance in agriculture.

Gross production value increased 11% from 2010 to 2016, but growth was achieved mainly through the continued expansion of production areas, not increases in productivity. In fact, productivity per agricultural worker has improved by a factor of only 1,6 in Africa over the past 30 years, compared with 2,5 in Asia.

Low productivity can be attributable to small-scale production, as well as lack of access to improved seeds and productivity-enhancing inputs such as equipment, fertilisers and pesticides. Low productivity and yield gaps are among the main constraints facing small- and medium-scale farmers, who account for more than 60% of Africa’s population.

Conversely, where carried out on a large scale under highly integrated value chains with established outgrower systems and sufficient investment, such as South Africa’s poultry or Kenya’s horticulture sector, production has been boosted and export capacity has been created. In most African countries, however, low levels of productivity have contributed to low and even decreasing levels of competitiveness.

Lack of competitiveness

Africa also lacks competitiveness at the processing stages of production. According to International Trade Centre data on African agricultural exports, less than 2% of cashew nuts, sesame seeds and tea, and around 6% of coffee was exported as processed goods in 2019.

More concerning, the rate of the total value of processed over unprocessed and semi-processed exports for all products showed a declining trend from 2010 to 2019.

Non-tariff measures represent another huge obstacle to Africa’s agricultural trade. Given poor infrastructure, high fuel costs and internal trade barriers, per-kilometre costs of trade within Africa remain very high. A recent study of 42 countries in sub-Saharan Africa found that median trade costs were over five times higher than elsewhere in the world.

In addition, the estimated costs of exporting agricultural products between African countries are generally higher than the costs of exporting outside the continent.

For example, the lowest trade cost (excluding tariffs) of exporting agricultural products from Nigeria to Lithuania is at about 155% of sales, while the lowest cost of exporting to another African country (in this case, South Africa) is at 188% of sales.

Enabling greater intra-regional trade, alongside increasing productivity and addressing other barriers to competitiveness, could play a central role in reversing Africa’s rising food import bill while boosting Africa’s position in the global market, stabilising prices, and securing the regional market supply of food.

With the African Continental Free Trade Area agreement (AfCFTA) in place, intra-African trade in agricultural products will potentially increase between 20% and 30% by 2040. By aggregating a huge market of more than 1,2 billion consumers, AfCFTA would provide attractive opportunities for both regional and international market players.

AfCFTA is an ambitious initiative, however, and its success will depend largely on ratification (only 30 countries out of 54 signatories had ratified it as of May 2020), and implementation. Africa’s experience with other regional trade agreements has been lacklustre, and there are thus mixed views on the outlook for Africa under a more complex AfCFTA.

For such a large regional arrangement to take effect, rigorous national measures and policies to address competitiveness at all links of agricultural value chains will be crucial.

These include measures to improve production capacities and promote investment for higher value-added agro-production. Ultimately, a robust intra-continental market information system will help connect surplus and deficit areas, opening up market access to help farmers reap the benefits of the single market created by AfCFTA.

According to the AfDB, an estimated US$315 billion (R5,18 trillion) will be needed between 2015 and 2025 to fulfil the potential transformation of African agribusiness. This will help unlock markets worth more than US$100 billion (R1,64 trillion) per year by 2025.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

This article is an edited excerpt from the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa’s ‘Africa Agriculture Status Report 2020: Feeding Africa’s Cities: Opportunities, Challenges, and Policies for Linking African Farmers with Growing Urban Food Markets’.